Oldal 225 [225]

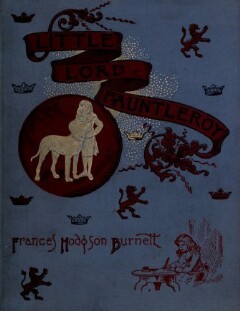

LITTLE LORD FAUNTLEROY 205

more pleased with his sons wife. It was true, as the people said,

that he was beginning to like her too. He liked to hear her sweet

voice and to see her sweet face; and as he sat in his arm-chair, he

used to watch her and listen as she talked to her boy; and he heard

loving, gentle words which were new to him, and he began to see

why the little fellow who had lived in a New York side street and

known grocery-men and made friends with boot-blacks, was still so

well-bred and manly a little fellow that he made no one ashamed of

him, even when fortune changed him into the heir to an English

earldom, living in an English castle.

It was really a very simple thing, after all,—it was only that he

had lived near a kindand gentle heart, and had been taught to think

kind thoughts always and to care for others. It is a very little thing,

perhaps, but it is the best thing of all. He knew nothing of earls

and castles; he was quite ignorant of all grand and splendid things ;

but he was always lovable because he was simple and loving. To be

so 1s like being born a king.

As the old Earl of Dorincourt looked at him that day, moving

about the park among the people, talking to those he knew and

making his ready little bow when any one greeted him, entertaining

his friends Dick and Mr. Hobbs, or standing near his mother or Miss

Herbert listening to their conversation, the old nobleman was very

well satisfied with him. And he had never been better satisfied than

he was when they went down to the biggest tent, where the more

important tenants of the Dorincourt estate were sitting down to the

grand collation of the day.

They were drinking toasts; and, after they had drunk the

health of the Earl, with much more enthusiasm than his name had

ever been greeted with before, they proposed the health of “ Little

Lord Fauntleroy.” And if there had ever been any doubt at all as to

whether his lordship was popular or not, it would have been settled