Page 196 [196]

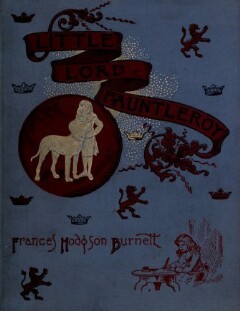

I76 LITTLE LORD FAUNTLEROY.

—— — e. — s — at — S —

rage and his determination not to acknowledge the new Lord

Fauntleroy, and his hatred of the woman who was the claimant’s

mother. But, of course, it was Mrs. Dibble who could tell the most,

and who was more in demand than ever.

‘An’ a bad lookout it is,” she said. "An if you were to ask me,

ma’am, | should say as it was a judgment on him for the way he s

treated that sweet young cretur as he parted from her child,— for

he s got that fond of him an that set on him an’ that proud of him

as he s a’most drove mad by what s happened. An what s more,

this new one s no lady, as his little lordship’s ma is. She s a bold¬

faced, black-eyed thing, as Mr. Thomas says no gentleman in livery

‘ud bemean hisself to be gave orders by; and let her come into the

house, he says, an he goes out of it. An’ the boy don’t no more

compare with the other one than nothin’ you could mention. An’

mercy knows what ’s goin’ to come of it all, an’ where it ’s to end, an’

you might have knocked me down with a feather when Jane brought

the news.”

In fact there was excitement everywhere at the Castle: in the

library, where the Earl and Mr. Havisham sat and talked; in the

servants hall, where Mr. Thomas and the butler and the other men

and women servants gossiped and exclaimed at all times of the day ;

and in the stables, where Wilkins went about his work in a quite

depressed state of mind, and groomed the brown pony more beauti¬

fully than ever, and said mournfully to the coachman that he “never

taught a young gen’leman to ride as took to it more nat’ral, or was

a better-plucked one than he was. He was a one as it were some

pleasure to ride behind.”

But in the midst of all the disturbance there was one person who

was quite calm and untroubled. That person was the little Lord

Fauntleroy who was said not to be Lord Fauntleroy at all. When

first the state of affairs had been explained to him, he had felt some