Oldal 158 [158]

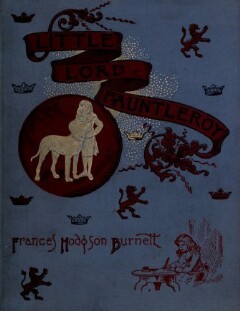

138 LITTLE LORD FAUNTLEROY.

=

doubt he was. At first he had only been pleased and proud of

Cedric’s beauty and bravery, but there was something more than

pride in his feeling now. He laughed a grim, dry laugh all to him¬

self sometimes, when he thought how he liked to have the boy near

him, how he liked to hear his voice, and how in secret he really

wished to be liked and thought well of by his small grandson.

‘“T’m an old fellow in my dotage, and | have nothing else to think

of,” he would say to himself; and yet he knew it was not that alto¬

gether. And if he had allowed himself to admit the truth, he would

perhaps have found himself obliged to own that the very things

which attracted him, in spite of himself, were the qualities he had

never possessed—the frank, true, kindly nature, the affectionate

trustfulness which could never think evil.

It was only about a week after that ride when, after a visit to his

mother, Fauntleroy came into the library with a troubled, thought¬

ful face. He sat down in that high-backed chair in which he had sat

on the evening of his arrival, and for a while he looked at the

embelb on the hearth. The Earl watched him in silence, wondering

what was coming. It was evident that Cedric had something on his

mind. At last he looked up. "Does Newick know all about the

people?” he asked.

‘It is his business to know about them,” said his lordship. " Been

neglecting it—has he?"

Contradictory as it may seem, there was nothing which enter¬

tained and edified him more than the little fellow’s interest in his

tenantry. He had never taken any interest in them himself, but it

pleased him well enough that, with all his childish habits of thought

and in the midst of all his childish amusements and high spirits,

there should be such a quaint seriousness working in the curly head.

‘There is a place,” said Fauntleroy, looking up at him with wide¬

open, horror-stricken eye— " Dearest has seen it; it is at the other