Page 130 [130]

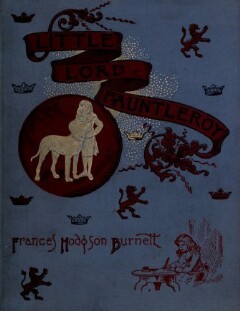

I IO LITTLE LORD FAUNTLEROY.

a ——_— = = —_— |S = SS =”

please himself and kill time as the days and years succeeded each

other; he saw this man, when the time had been killed and old age

had come, solitary and without real friends in the midst of all his

splendid wealth; he saw people who disliked or feared him, and

people who would flatter and cringe to him, but no one who really

cared whether he lived or died, unless they had something to gain

or lose by it. He looked out on the broad acres which belonged to

him, and he knew what Fauntleroy did not — how far they extended,

what wealth they represented, and how many people had homes on

their soil. And he knew, too,— another thing Fauntleroy did not,—

that in all those homes, humble or well-to-do, there was probably

not one person, however much he envied the wealth and stately

name and power, and however willing he would have been to possess

them, who would for an instant have thought of calling the noble

owner "good," or wishing, as this simple-souled little boy had, to

be like him.

And it was not exactly pleasant to reflect upon, even for a cyni¬

cal, worldly old man, who had been sufficient unto himself for sev¬

enty years and who had never deigned to care what opinion the

world held of him so long as it did not interfere with his comfort

or entertainment. And the fact was, indeed, that he had never

before condescended to reflect upon it at all; and he only did so now

because a child had believed him better than he was, and by wishing

. to follow in his illustrious footsteps and imitate his example, had

suggested to him the curious question whether he was exactly the

person to take as a model.

Fauntleroy thought the Earl’s foot must be hurting him, his

brows knitted themselves together so, as he looked out at the park;

and thinking this, the considerate little fellow tried not to disturb

him, and enjoyed the trees and the ferns and the deer in silence.

But at last the carriage, having passed the gates and bowled