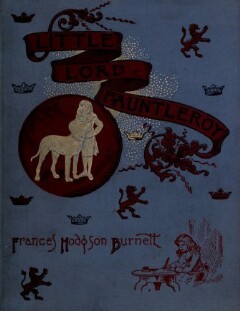

Page 101 [101]

LITTLE LORD FAUNTLEROY. 81

flushed little face. When they entered the room where they were

to dine, Cedric saw it was a very large and imposing one, and that

the footman who stood behind the chair at the head of the table

stared very hard as they came in.

But they reached the chair at last. The hand was removed

from his shoulder, and the Earl was fairly seated.

Cedric took out Dick s handkerchief and wiped his forehead.

“It’s a warm night, is n't it?” hesaid. ‘Perhaps you need a fire

because — because of your foot, but it seems just a little warm to me.”

His delicate consideration for his noble relatives feelings was

such that he did not wish to seem to intimate that any of his sur¬

roundings were unnecessary. —

‘You have been doing some rather hard work,” said the Earl.

“Oh, no!” said Lord Fauntleroy, “it was nt exactly hard, but |

got a little warm. A person will get warm in summer time.”

And he rubbed his damp curls rather vigorously with the gor¬

geous handkerchief. His own chair was placed at the other end of

the table, opposite his grandfather’s. It was a chair with arms, and

intended for a much larger individual than himself; indeed, every¬

thing he had seen so far,—the great rooms, with their high ceilings,

the massive furniture, the big footman, the big dog, the Earl him¬

self,—were all of proportions calculated to make this little lad feel

that he was very small, indeed. But that did not trouble him; he

had never thought himself very large or important, and he was quite

willing to accommodate himself even to circumstances which rather

overpowered him.

Perhaps he had never looked so little a fellow as when seated

now in his great chair, at the end of the table. Notwithstanding

his solitary existence, the Earl chose to live in some state. He

was fond of his dinner, and he dined in a formal style. Cedric

looked at him across a glitter of splendid glass and plate, which to

6