Oldal 71 [71]

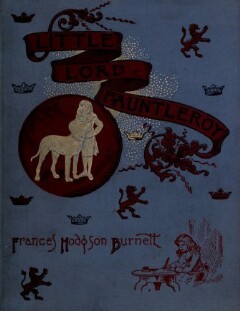

LITTLE LORD FAUNTLEROY. 5I

— — a illir e e B a dik eee i ee mas — —— mille ie MANNER TRENT MRNRSRRÉÉSÉSMTB 7

sat down and nursed his knee with his chubby hands, and conversed

with much gravity, he was a source of great entertainment to his

hearers. Gradually Mr. Havisham had begun to derive a great deal

of private pleasure and amusement from his society.

‘“And so you are going to try to like the Earl,” he said.

" Yes, answered his lordship. "He s my relation, and of course

you have to like your relations; and besides, he ’s been very kind

to me. When a person does so many things for you, and wants you

to have everything you wish for, of course you d like him if he was

nt your relation; but when he ’s your relation and does that, why,

you re very fond of him.”

“Do you think,” suggested Mr. Havisham, “that he will be fond

of you?”

‘“ Well,” said Cedric, "I think he will, because, you see, I m his

relation, too, and I ’m his boys little boy besides, and, well, don’t

you see—of course he must be fond of me now, or he would nt

want me to have everything that I like, and he would nt have sent

you for me.”

- Oh!” remarked the lawyer, "that ’s it, is it?”

“Yes,” said Cedric, "that sit. Don’t you think that ’s it, too?

Of course a man would be fond of his grandson.”

The people who had been seasick had no sooner recovered from

their seasickness, and come on deck to recline in their steamer-chairs

and enjoy themselves, than every one seemed to know the romantic

story of little Lord Fauntleroy, and every one took an interest in the

little fellow, who ran about the ship or walked with his mother or the

tall, thin old lawyer, or talked to the sailors. Every one liked him ;

he made friends everywhere. He was ever ready to make friends.

When the gentlemen walked up and down the deck, and let him

walk with them, he stepped out with a manly, sturdy little tramp,

and answered all their jokes with much gay enjoyment; when the