Stranica 28 [28]

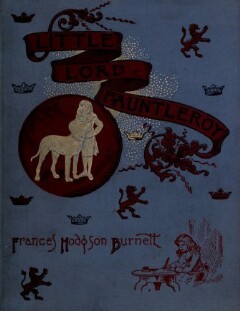

$ LITTLE LORD FAUNTLEROY.

i

his shoulders. She was willing to work early and late to help his

mamma make his small suits and keep them in order.

‘Ristycratic, is it?” she would say. ‘ Faith, an I d loike to see

the choild on Fifth Avey-zoo as looks loike him an shteps out as

handsome as himself. An’ ivvery man, woman, and choild lookin’

afther him in his bit of a black velvet skirt made out of the mis¬

thress’s ould gownd; an his little head up, an’ his curly hair flyin’

an’ shinin’. It’s loike a young lord he looks.”

Cedric did not know that he looked like a young lord; he did

not know what a lord was.. His greatest friend was the groceryman

at the corner—the cross groceryman, who was never cross to him.

His name was Mr. Hobbs, and Cedric admired and respected him

very much. He thought him a very rich and powerful person, he

had so many things in his store,—prunes and figs and oranges and

biscuits,—and he had a horse and wagon. Cedric was fond of the

milkman and the baker and the apple-woman, but he liked Mr.

Hobbs best of all, and was on terms of such intimacy with him that

he went to see him every day, and often sat with him quite a long

time, discussing the topics of the hour. It was quite surprising how

many things they found to talk about—the Fourth of July, for

instance. When they began to talk about the Fourth of July there

really seemed no end to it. Mr. Hobbs had a very bad opinion of

“the British,” and he told the whole story of the Revolution, relat¬

ing very wonderful and patriotic stories about the villainy of the

enemy and the bravery of the Revolutionary heroes, and he even

generously repeated part of the Declaration of Independence.

Cedric was so excited that his eyes shone and his cheeks were red

and his curls were all rubbed and tumbled into a yellow mop. He

could hardly wait to eat his dinner after he went home, he was so

anxious to tell hismamma. It was, perhaps, Mr. Hobbs who gave

him his first interest in politics. Mr. Hobbs was fond of reading the